Lesson

Syriac Scripts - Melkite

Description

The distinctive script used by Chalcedonian Syriac Christians.

Overview

The so-called Melkite script is found much less often than Estrangela, Serto, or East Syriac, but enough manuscripts survive to reveal its distinctiveness from the three other better known types of writing.

The term “Melkite” (malkā) refers to adherents of the Council of Chalcedon particularly in areas where there where also adherents of miaphysite belief. Melkite, or Rum Orthodox, Christians are partly an heir to Syriac culture, and Syriac was used liturgically into the eighteenth century in some places. (In Palestine and Transjordan from the 5th-14th centuries, Chalcedonian Christians used an Aramaic dialect altogether distinct from Syriac, Christian Palestinian Aramaic [CPA], the script of which has some similarities to Estrangela.) From the ninth century especially, the literature is in Arabic, but in Syriac there are some theological and polemical texts, not to mention a number of translations from Greek, as well as a few monastic texts known from Melkite manuscripts but originating in Syriac Orthodox or Church of the East communities. (For Syriac, see further Brock in GEDSH, 285-286, and “Melkite” and “Melkites” in the Comprehensive Bibliography of Syriac Christianity at the Hebrew University of Jerusalem; for Arabic, see G. Graf, GCAL I 623-640, II 3-93, and III 23-41, 79-298, and J. Nasrallah, Histoire du mouvement littéraire dans l’Église Melchite du Vᵉ au XXᵉ siècle, 4 vols.)

According to Hatch (An Album of Dated Syriac Manuscripts, 28-29), the Melkite Syriac script developed from Serto, but he generally points out similarities with Estrangela and East Syriac, too, echoing Wright, who says that it “inclines in many points towards the Nestorian” (Cat. Syr. Brit. Mus., pt. III, p. xxxi). Plates xv-xvii of Wright’s catalog provide some examples. Hatch knew of only fourteen manuscripts, including those in Wright’s catalog, in Melkite script clearly dated before the end of the sixteenth century, the cutoff point for his Album. The oldest of these manuscripts is one finished at the Lavra of Mar Elias on the Black Mountain and dating from 1045 CE. Hatch offers examples in his plates clxxxiv-cxcvii. The examples below from various collections add to those already known from Wright and Hatch.

Example 1 - 14th/15th-century manuscripts

Mardin, CCM 147, f. 2r (14th/15th C.)

Menaion for September

Mardin, Chaldean Cathedral, CCM 147, f. 2r. All rights reserved. Image provided by HMML.

| ālap | a vertical line, often with the top angling back to the right |

| gāmal | as in East Syriac, i.e., an angled line reaching below the baseline |

| dālat / rēš | like East Syriac shape, i.e., the letter has a baseline |

| hē | the East Syriac/Serto shape |

| wāw | completely round, as in Serto |

| kāp | in final form, like the East Syriac shape (similar to Estrangela, but with the top left segment curving back to the right), and with the descender pointing leftward |

| mim | the round shape of East Syriac and Serto |

| qop | angular, not round |

| tāw | the Estrangela type with a thick line instead of a more open loop on the bottom left, as well as the triangular shape; the former occurs when not joined to the previous letter, both can occur when joined to the previous letter |

Example 2 - 16th-century manuscripts

Mhadsei, MHAY 1, ff. 4v-5r (dated 1512)

Gospel Lectionary

Mhadsei, Church of the Theotokos, MHAY 1, ff. 4v-5r. All rights reserved. Image provided by HMML.

| ālap | in both the Estrangela shape (with the right leg, not the left, hanging below the line) and the single line type of Serto and East Syriac, the top angling back to the right; this line type is rather curvy sometimes |

| dālat / rēš | of the Serto shape |

| hē | with the right vertical reaching below the line, and when joined to the previous letter, the joining line attached to the hē rather high on that vertical, not at the bottom |

| wāw | often a circle, but sometimes an almost closed loop |

| hē-wāw | the ligature for the combination hē-wāw (e.g. f. 4va, lines 4 and 7 from the bottom, and f. 4vb, lines 5 and 6), which, however, is not always employed. |

| mim | boxy, but with slightly rounded corners the final form is not quite closed, and the descender, thin and angling off to the left |

Diyarbakir, DIYR 62, f. 42r (dated 1535)

Menaion

Diyarbakir, Meryem Ana Syriac Orthodox Church, DIYR 62, f. 42r. All rights reserved. Image provided by HMML.

| ālap | like Serto |

| gāmal | as in Estrangela |

| dālat / rēš | like East Syriac shape, i.e., the letter has a baseline |

| hē | of the Serto shape |

| wāw | completely round, as in Serto |

| kāp | in final form, like the East Syriac shape (similar to Estrangela, but with the top left segment curving back to the right), and with the descender pointing leftward |

| mim | of the angled, square shape, as in Estrangela, usually closed |

| qop | angled, not round |

| tāw | a shape also known in East Syriac: a form similar to Estrangela, but with a thick line instead of an open loop on the left |

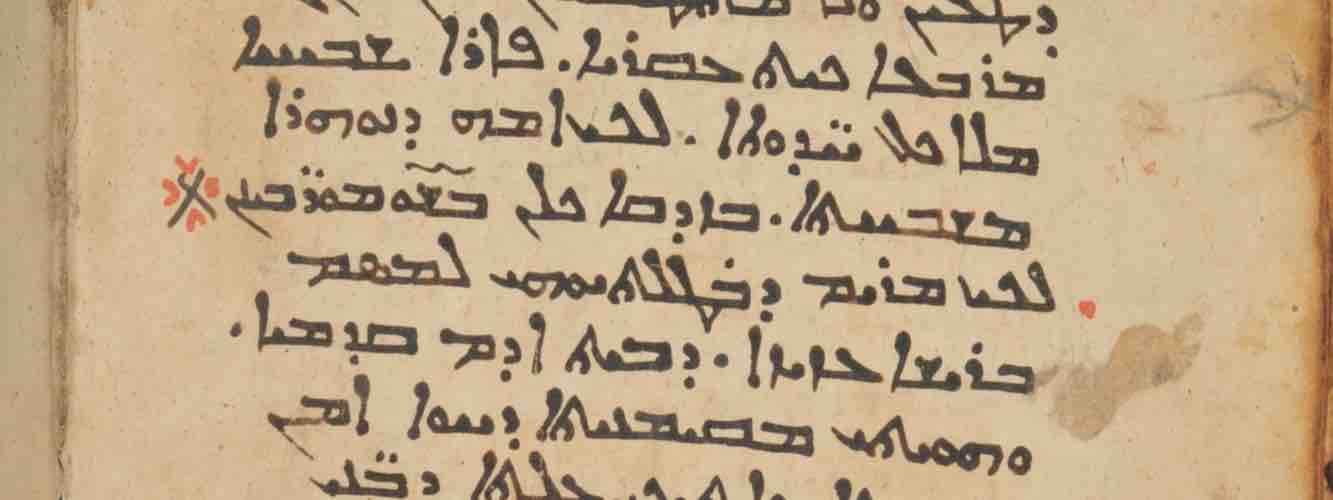

Diyarbakir, DIYR 83, f. 35v (dated 1540)

Pentecostarion

Diyarbakir, Meryem Ana Syriac Orthodox Church, DIYR 83, f. 35v. All rights reserved. Image provided by HMML.

| ālap | generally the line type, but at line-end the Estrangela type may occur |

| dālat / rēš | of the East Syriac type |

| hē-wāw | ligature seen in MHAY 1 is also present here, e.g. line 10 (bis) and the last line. |

| zayn | hanging below the line |

| mim | angular, not round |

| šin | a pronounced triangular shape |

| tāw | of the closed-loop Estrangela type |

Mardin, CCM 102, f. 1v (dated 1583)

Hymns for Passion and Easter Week

Mardin, Chaldean Cathedral, CCM 102, f. 1v. All rights reserved. Image provided by HMML.

| ālap | of the line type, but curvy, as in MHAY 1 |

| dālat / rēš | often of the East Syriac type |

| mim | boxy not quite closed when final |

| tāw | when of the closed-loop Estrangela type, may have a small loop at the top |

Diyarbakir, DIYR 63, f. 69v (16th century)

Menaion

Diyarbakir, Meryem Ana Syriac Orthodox Church, DIYR 63, f. 69v. All rights reserved. Image provided by HMML.

| ālap | of the line type, with a heavy backward lean |

| dālat / rēš | often of the Serto type, but the East Syriac type also occurs |

Example 3 - 16th/17th-century manuscripts

Diyarbakir, DIYR 335, f. 157v (16th/17th century)

Menaion

Diyarbakir, Meryem Ana Syriac Orthodox Church, DIYR 335, f. 157v. All rights reserved. Image provided by HMML.

This manuscript shows few features that we have not seen before, but note the overall compact footprint of each letter. In addition, note the sideways writing of the word ḥassāmā’it at line-end at f. 157vb, line 6 from the bottom.

Hamatura, HMTR 26, ff. 10v-11r (dated 1605)

Gospel Lectionary with Commentary

Kūsbā, Monastery of the Theotokos, HMTR 26, ff. 10v-11r. All rights reserved. Image provided by HMML.

| ālap | in both types, the Estrangela form (with a curly top) especially at line-end the right leg of the Estrangela type hanging below the line |

| bēt | and qop much wider than other letters |

| hē | with the vertical hanging below the line |

| ḥēt and yod | sharp tooth-like shapes very thick at the bottom |

| ṭēt | not as tall as ālap or lāmad |

| kāp | with a ductus more like that in Serto than East Syriac |

| lāmad | in final form, not quite the double-line seen in Serto, but a long tail, slightly freer, almost paralleling the first stroke of the letter |

| mim | neither round, nor quite square or rectangular, but almost trapezoidal |

The hand of this manuscript shows a bit more variation in line thickness than other Melkite manuscripts.

At word-end, letters that would end in a line at baseline (e.g. bēt, šin) often have a high, sharp uptick. At or just before line-end, letters or connectors may be stretched to fill the line.

Ready to transcribe?

Try your hand at transcribing Melkite scripts