Transcribe

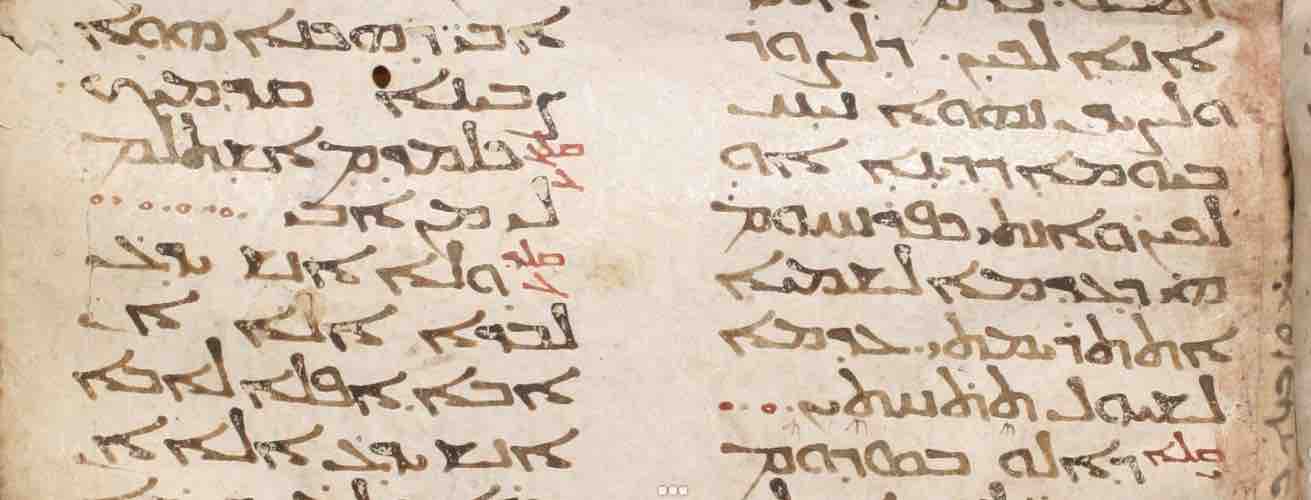

Syriac Basics - Transcription

Description

Syriac script has served not only for writing Syriac and Neo-Aramaic, but also for several non-Aramaic languages, including Armenian, Turkish, and Persian.

Overview

Syriac handwriting typically requires less deciphering than Latin, Greek, and Arabic scripts. The following exercises offer some practical exercises in rendering what’s on a manuscript page into a document easily readable by humans and computers. This allows you and others to focus on the text itself, rather than on the script, which may or may not be clearly legible. (A more complex and more versatile way of doing this is with TEI. See A TEI-Based Tag Set for Manuscript Transcription.)

In addition, having a complete and accurate transcription means you have a reliable record of the manuscript’s witness. Nowadays, most of us have easy access to digitized images either online or on our own hard drives, but there may still be cases where having a transcription will be the only record of a manuscript (just as later copies of an ancient manuscript are often the only witnesses to the lost exemplar). Finally, having transcribed a manuscript means that you have correctly read the letters that are written, or at least made the initial attempt to do so, and noted any possible problems in the text.

In transcribing a manuscript, the fundamental practice is to copy the letters (and other marks, as much as possible) as they are in the manuscript, with line breaks (and, of course, column, page, and folio breaks) indicated. A transcription may also require the use of a few signs (brackets, braces, angular braces, parentheses, obeli) to indicate (and complete) abbreviations, obvious errors, missing letters (or words), etc. (For further information, see the "Basics" section of vHMML's Transcribing Latin Manuscripts, as well as Martin L. West, Textual Criticism and Editorial Technique. Applicable to Greek and Latin Texts, [Stuttgart, 1973], pp. 80-82, and much more concisely, the outline here: Commonest Abbreviations, Signs, etc. Used in the Apparatus to a Classical Text [PDF]). Marginalia may be indicated between \\ and //, insertion of letters or words on the line between / and \, interlinear insertions between \ and /. These signs may, of course, disrupt the continuity of Syriac letters in a word, something that is not a problem in Latin, Greek, Hebrew, and other scripts that do not have connected letters. By the way, there is nothing inherently wrong with transcribing a Syriac manuscript using a consistent transliteration, rather than Syriac letters, although this is more difficult for the dots.

Transcribing the consonants is straightforward enough, but we must consider a few issues in addition to recording the letter-forms themselves. First, Syriac scribes use abbreviations — suspensions, that is, with the beginning of the word written and a line over the last letter[s] to show that something is not written — although not nearly as often as in some other traditions. As mentioned above, they may be completed within parentheses.

What about vowels and the various dots that appear in Syriac manuscripts? Many Syriac manuscripts have no vowels or few vowels, and it is not always certain if the vowels found in a manuscript were written by the scribe or a later reader (not that a later reader’s vowels are of no interest!). In large measure, whether or not to record vowels depends on the kind of text (and even the word) and on the kind of edition planned, if one is planned. Vowels in poetry and in grammatical and lexical works may be very meaningful, and in any kind of text more unfamiliar words, including some proper names, may have vowels that a transcriber should note.

There are three broad functions of dots in Syriac: phonological (rukkākā and quššāyā); grammatical (to mark 3fs suffix, participle, syāmē, etc.); for punctuation (to mark stronger or weaker divisions between sentences and parts of sentences). Syriac grammarians discussed these dots, and some details will also be found in the larger grammars of modern scholars (e.g. Th. Arayathinal, Aramaic Grammar, vol. 1, pp. 26-45; G. Kiraz, Turrāṣ Mamllā: A Grammar of the Syriac Language, vol. 1, Orthography, chapters 4-6). J.B. Segal (The Diacritical Point and the Accents in Syriac) and, very recently, Kiraz (The Syriac Dot) have devoted monographs to these matters. In addition to these guides, some of which may present an ideal rather than the reality, interested readers must carefully study manuscripts themselves. All things being equal, transcribers should record these dots as they stand in the manuscript.

Note: for the PDF reference above, if you do not already have PDF viewer software you may download the free Adobe Acrobat Reader.